How cars took over the streets

I love cars. I think they are fun, comfortable, and sometimes even an extension of home. I grew up loving them and having my first car was nothing short of a suburban coming-of-age daydream.

Then I actually grew up, moved to a city, and the bubble burst.

It wasn’t until I lived in a walkable city with decent public transport and cycling infrastructure that I realized cars are not the supreme mode of transport. Cars are not the best tools for mobility, nor the most efficient. Yet, most cities today seem to be built around them. So I took a dive to see how this happened.

Originally published on Substack. Get every post on TheEndNote delivered to your email by subscribing here.

A brief timeline of human (ground) mobility

It starts with just a group of apes who were brave enough to walk around on two feet with their backs straight.

Then we domesticated animals and they helped us move around and carry stuff.

Then came the wheel and boy were we movin..

At that point someone asked, what if we put horse and wheel together, and so we had chariots and carriages and stagecoaches.

So from around 2,500 BCE* to the early 1800s, horses and their derivatives were the dominant mode of transport.

But in 1804, the first steam-powered train was introduced, leading to widespread railway expansion.

The horse was finally faced with some competition. Or some relief maybe?

The differences between one method and the other were distant enough for each to get their own place and happily coexist.

But as the industrial revolution continued, another invention would come to change everything.

The bicycle.

In 1817, the ‘Draisine’ or Dandy Horse would appear as an early ancestor of the bike. Didn’t really catch on, but something sparked.

By the 1870s, it evolved into the Penny-Farthing (that high-wheel sketchy bicycle ridden by rich mustached men you’ve probably seen somewhere). However, that was still too inconvenient and dangerous for more than a few enthusiasts to adopt it.

But finally, by 1885, we would get the safety bicycle (the bicycle as we know it), featuring equal sized wheels, a chain drive and pneumatic tires. Now everyone wanted one. And what started as the craze of a few wealthy people, led to the first bicycle boom in the 1890s.

Bicycle prices dropped and became accessible for the working class. These were machines of freedom and liberation, in fact, bicycles played a role in the women’s suffrage movement, increasing mobility dramatically as it offered the first vehicle choice for unchaperoned travel.

Yet we don’t see much of the bike in historical films or other culture. This, (among other reasons we’ll see in the next section) because the reign of the bike wouldn’t last long, as the rise of the car came to terrorize everyone by the early 1900s.

But the bike and the car were not always enemies. In fact, according to Carlton Reid’s Roads were not built for cars their stories are deeply intertwined.

The car and the bicycle—a story of love and betrayal

It’s easy to assume that the car evolved from the horse-drawn carriage, and that the bicycle was some distant divergent cousin. But that’s not the case.

As we saw, at some point bicycles were it. And so they were because the invention carried interest, and abundant funding for development. The bicycle caught the attention of some very rich enthusiasts, and some of the most powerful among them would go on to create the League of American Wheelman.

These guys were all about their bikes. They pushed for better roads so they could ride them really fast and for longer distances. They wanted to sell more bikes too.

So they started the famous “Good Roads Movement” in the US. As Carlton Reid explains, the road revolution in America was started by cyclists, not motorists.

The problem? They were the same people.

A few names of early bicycle enthusiasts include the Dodge brothers, Louis Chevrolet, Henry Ford, Lionel Martin… Sound familiar?

What happened then?

Bicycle technology kept evolving and so the first car was born not from the horse-drawn carriage, but from the bike. I mean… look at her!

That’s a bike. More specifically, it is the Benz Patent-Motorwagen (yes, as in Mercedes Benz). It is also considered the first practical automobile.

And these wheelmen were all about it.

So their newfound obsession with bikes was quickly redirected towards building automobiles. They already had most of the tools for it, as a great part of the technology in early vehicles came from the bike, so they left the latter behind. Reid suggests some of them would be baffled to find out we’re still riding them today. To them, bicycles were just a transitional step towards automobiles. What’s more, as the bicycle became accessible and turned into the working-class vehicle, these former wheelman lost all interest in being associated with it. And so, they wrote it off their history and stamped the car on top.

However, the rise of the car did not happen overnight.

Looking into the evidence provided in Peter Norton’s Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, the rise of the car wasn’t natural, organic, and inevitable, it came with strong resistance from the people and it was pushed by a mix of social pressures, economic incentives, and aggressive corporate lobbying.

The wheels of freedom—the car’s sleazy race to the top

In Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, Peter Norton guides us through the history of how American cities chose cars over everything else.

More importantly, he explains what it took for the perception of these vehicles to go from “loud, stinky, deadly machines”, to become the norm, even when “more pedestrians were killed by cars in the first four years after World War I, than all 50,000 American servicemen who died fighting in France”. That’s a lot of people. Most of these were kids, to whom the streets belonged, to roam and play before the car came in.

But how could they let this happen? Well, it’s key to remember how the early motorists (once cyclists) were rich and powerful men, and we don’t have to look far to understand how this works. Just a look at any piece of recent news will show you how when a rich and powerful man is convinced he is saving us, it’s very hard to convince him that he is, in fact, killing us. No matter how much science and reason you bring as proof.

Norton explains how pedestrians were pushed off the streets and how these were reclaimed by cars, who time and time again would find ways to refuse restrictions. Instead, the car PR strategy relied on throwing blame around, coining terms like reckless drivers and jaywalking, and ridiculing those who did not adapt to their new rule, instead of acknowledging the car as a dangerous machine. Even today, as noted in this article from Rage Climatique (originally in French) “Drivers are often blamed for road accidents, but the fact remains that, on average, year after year, 20 times more people die in road accidents than in public transit accidents. So it’s not the drivers who are dangerous, but the automobile as a means of transport.”

Still, it took more than a bit of bullying—and billions of dollars for the car to become the norm.

It was a domino effect too.

Rail transit was the backbone of many cities. From railways to streetcars. But these were dismantled to make more space for cars, leaving little options for travelling around without one.

Then the billions that went into highway expansion, under the idea of the car-centric futuristic connected cities, left little budget to fund public transport.

Then zoning laws and urban sprawl divided homes from workplaces and commercial areas, making walking or cycling impractical in cities under this urban style.

And finally, the coup-de-grace came from the same place most of our worries today come from: Cultural conditioning. The post-war boom and the myth of the American dream included a car. Correction. It started with one. American freedom was brought to you by the Mustang, the Cadillac, the pickup truck, the freedom machines. If you didn’t own a car, to the eyes of the Madison Street man, you were nothing.

Just as everything else that came with the lifestyles promoted by the Coca-cola ads of the 50s, it worked for a very short period of time and for a very small group of people. But we all endure the consequences.

Shifting lanes

So “people” “chose” cars. And now, traffic in cities around the world is way past the point of unsustainability. Cities simply don’t have the capacity for mass car ownership. The “just one more lane” mentality has proven useless time and time again, yet we keep gutting public spaces to make more space for cars.

Some brave cities have dared to go the other way, experimenting with alternative mobility practices.

Road diets, for example, are a technique in city planning where lanes in specific areas are reduced or canceled to make space for other means of transport.These experiments across the world have proved better for mobility.

Research shows that by reallocating road space for bikes, pedestrians, and public transit, cities can reduce crashes, improve commercial activity, and make streets more livable (and enjoyable)—without increasing congestion or affecting emergency response times.

So why are we not doing more of this?

Well, change would require money and time. Not as much of either as it took to build car-centric cities though. However, the excuse fuels a small but loud group of people who can’t see past their own comfort. A group that cares more about parking spots than safe and enjoyable public spaces, not realizing how these inconveniences for them only reveal one thing:

Cars were never meant to be the default.

They were forced into dominance by decades of lobbying, billions of dollars, and cultural conditioning meant to benefit no one but the brands selling them. It was maybe not an ill-intentioned plan, but it’s about time we accept it was misguided. We are not trying to push cars aside or “ban your cars”, we are just trying to level the playing field.

And I insist, I think cars can be great. They are very comfortable and excel at certain tasks in mobility that other modes of transport simply can’t do as well.

But for most daily tasks, especially within a city, cars are objectively inefficient.

Because if making space for others is conflicting so much with driving, could it be that driving was never that good in the first place?

We need to move. It’s just human. We need better planned urban spaces and we need space for every need of mobility. Cities should be accessible for everyone. Cars included. But there’s a time and a place for them and it’s just not everywhere, all the time.

Is it too radical to think that cities should be built around people and not machines? Just like any other technology, we should learn to use the car—to choose it. Not to depend on it.

P.S. (Fuel to the fire):

I was just about to publish this article when I serendipitously came across the Winter 2024 Journal de Rage Climatique. In this edition, the collective featured three well-developed, rigorously argumented articles that further debunked car culture. Fortunately, I found these before publishing, and to my delight, they have web versions available to, so I’m linking to them here:

- Crush Car Culture With Free and Expanded Public Transit!

- Terrasser la culture du char à grands coups de Kryptonite (Crushing car culture with heavy blows of Kryptonite) (French only)

- Pour un transport inclusif: oublions la voiture (For inclusive transportation: let’s forget the car) (French only)

Sources:

* Other sources date to 4,000 BCE, however, I’m using dates according to new science better explored by William T. Taylor in his book Hoof Beats: How Horses Shaped Human History (2024))

Books mentioned in the article:

- Peter Norton’s Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City

- Carlton Reid’s Roads were not built for cars

Interview with Carlton Reid:

- Off Peak | Web Archive — Episode 2: Roads Were Not Built for Cars

Lectures:

- Carlton Reid Lecture: Roads Were Not Built for Cars lecture

- Vince Graham YT channel: Fighting Traffic by Peter Norton

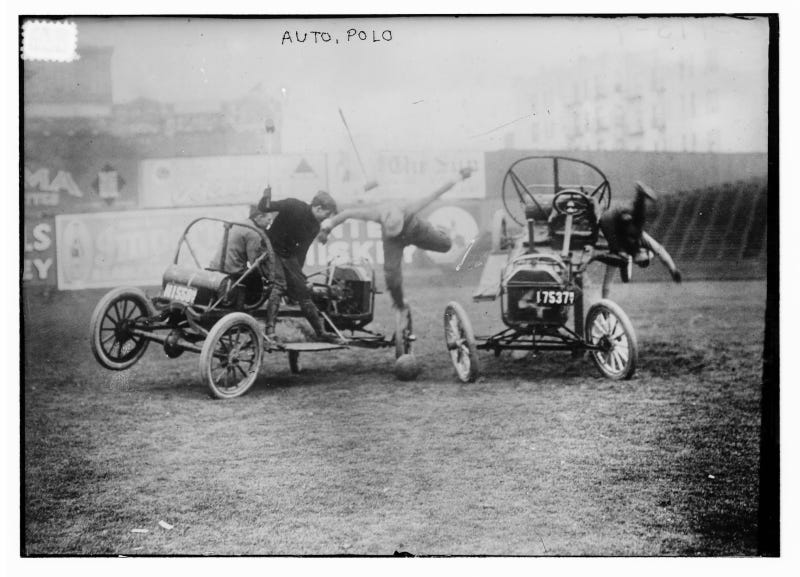

Featured image: “Auto Polo” Bain News Service (1912)

Leave a Reply